I was recently asked if I had ever written an essay on my “primitivist philosophy.” I don’t consider myself a primitivist, and I don’t know if I even have a fully coherent philosophy when it comes to technology and its use, but my thinking on the topic has certainly evolved and deepened since I last wrote on the topic here. Reading and learning on many topics has effected my views, including philosophy, permaculture, responsible agriculture, history, economics, and religion. I can’t condense the contents of many books into one essay, so this post will just scratch the surface of what people more intelligent than I have written.

Let’s start with the 5 questions for evaluating technology I posed back in 2014:

- What benefit will I gain from making use of this technology?

- How much will it cost me to make use of this technology?

- If I adopt this technology, am I in a worse place when/if it fails than I would be if I had never adopted it?

- Should this technology fail, is it easier or harder to repair myself than my current system?

- Will the regular use of this technology cause me to lose a skill that would be vital should the technology fail?

All the above questions are focused on evaluating a newly-available technology. But what about previously-adopted technologies? Things I’ve been using since birth? Should they also be evaluated?

Some rather ubiquitous technologies, adopted by many of my peers from birth, I grew up largely or completely without. I grew up largely without television, and completely without video games. Even today, in my thirties, I still do not own a television. I’ve noticed that this results in me having a completely different perspective on the technology than some of my peers. When a peer and I discuss the role of television, particularly national broadcasts, in the destruction of regional dialects and local cultures, we interpret this fact differently. He sees it as a sad but inevitable loss, because of course we couldn’t live without television. I see it as a needless and wanton destruction, because of course television is unnecessary and this negative consequence far outweighs any minor entertainment value when there are so many more enjoyable means of entertainment anyways.

Perhaps it was recognizing the negative effects of an ubiquitous technology that I don’t use, like television, that prepared me to see the negative effects of technology that I do use, like cars. I don’t think I’d ever even considered the cultural impact of cars until I read this short article in 2017. But suddenly, a lot of things clicked. The unwalkability of modern cities. The much stronger social fabric (and better aesthetics) of walkable cities. The insanity of transporting food across a continent . But mostly, I suddenly woke up to the cultural and societal shifts that the automoble brought about. Perhaps I was primed here too. In 2017, my wife and I shared a single vehicle, and had done so since getting married in 2015. When she went out of state to visit her parents, I rode my bicycle to work. Perhaps this helped me to see the possibility of living without a car (a possibility that I am not currently pursuing, more on that later), and perhaps I had to see living without a car as possible to honestly consider the damages caused by the mass adoption of the automobile.

Somewhere around 2017, I began looking for a grain mill. My wife makes homemade bread, and I wanted to mill our own flour, rather than buying flour. I was going to buy an electric grain mill, like both my mother and Courtney’s mother had when we were growing up. But then we happened to buy a hand-crank coffee grinder. I discovered that I enjoyed turning the crank by hand. And I’d always hated the terrible racket that electric grain mills make. I did some research, and found a number of hand-cranked grain mills, eventually buying one. I found several things that surprised me. First, I was surprised that the mill was far easier to turn than I expected. My 2 year old at the time was able to turn it. Second, I was surprised at how fast it was. It milled enough flour to bake a batch of bread almost as fast as the electric mill I was used to–and ground it finer to boot! Third, I was surprised at how much more enjoyable it was to grind grain using it than with the electric mill. Sure, it took a few seconds longer, but the whole process was enjoyable, while the sightly faster process with the electric mill was not.

Previous to the grain mill, in 2016 when we bought our first house, I couldn’t afford to buy a riding mower. So I bought a Fiskars reel mower and mowed our just under half acre lot with it until a friend later gave me a riding mower. I loved mowing with it. It took a little while, and it was hard to push if I let the grass grow too long but it did a great job, and it was so quiet, and it didn’t matter if the grass was wet. Sometimes I mowed at 6am without worrying about disturbing the neighbors. Later, when I was given the rider, I spent far less time mowing, but it also was less enjoyable, a chore to finish. And my lawn never looked as nice. Having had this experience with the lawn mower, coffee grinder, and now the grain mill, I began to consciously choose to use hand tools more on projects and power tools less. I found that this often made the projects more enjoyable. They did take longer, but I also tended to procrastinate starting less, so I didn’t find this really impacted the total amount of work I got done.

Even after I began choosing to use hand tools more than power tools, there was one particular power tool or machine that I wanted. I have wanted a small farm since at least my teens. This farm would be diversified and labor-intensive, making use of small fields that are too small to even work with modern 24-row cultivators. And I wanted a compact or sub-compact tractor with a front-end loader to work this small farm. A front-end loader is an incredibly useful piece of equipment, with essentially limitless uses. There is also not a human or animal powered alternative to a front-end loader. But then I started realizing the harm caused by tractors.

Tractors, by allowing one man to do much more work, greatly reduced the jobs available in agriculture, and were thus instrumental in forcing many men off of farms and into the cities and factories. As the tractors grew larger, so did this dysgenic effect. Furthermore, tractors were instrumental in degrading the land, and in exceeding natural limits, causing monopoly of the food supply as more small farmers are forced out of business each year as larger and larger corporations control more and more of the land. Reading The Unsettling of America by Wendell Berry convinced me that when I finally get my little farm, draft animals will be better for both me and the land than a small tractor.

The fields lose their humus and porosity, become less retentive of water, depend more on pesticides, herbicides, chemical fertilizers. Bigger tractors become necessary because the compacted soils are harder to work-and their greater weight further compacts the soil. More and bigger machines, more chemical and methodological shortcuts are needed because of the shortage of man-power on the farm—and the problems of overcrowding and unemployment increase in the cities. It is estimated that it now costs (by erosion) two bushels of Iowa topsoil to grow one bushel of corn. It is variously estimated that from five to twelve calories of fossil fuel energy are required to produce one calorie of hybrid corn energy.

The Unsettling of America by Wendell Berry

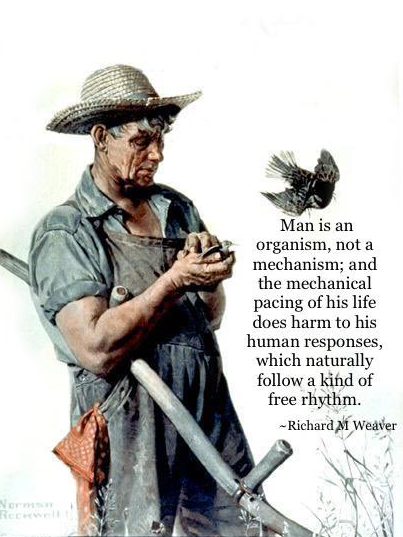

Philosophically, there are few things that I have learned that have changes how I view and interact with technology. The first is that technology is not neutral. Most of us recognize that every tool or machine has a purpose, but most of us do not see the actual purpose of most technology. For example, if you ask most people the purpose of a gas-powered hydraulic log splitter, they will say that its purpose is to split logs. However, this is not the case. The purpose of a splitting maul is to split logs. The purpose of a gas-powered hydraulic log splitter is to free the splitting of logs from the constraints of human labor. If human limits are a fundamental part of humanity, than machines designed to circumvent those limits are fundamentally inhuman, and we shouldn’t be surprised if they also circumvent other aspects of humanity, including community and sometimes joy.

Secondly, I’ve learned to see labor differently. This is two-fold. First, I’ve learned that labor isn’t a negative to be avoided at all costs, and second, I’ve learned to more fully account for hidden labor. Much of our technology is designed with an assumption that labor is bad. The gas-powered hydraulic log splitter is “better” than the splitting maul because it requires less labor. But, as I learned with my grain mill and lawn mower, not all labor is equal. Some labor is more enjoyable than other labor. I could split my logs with a hydraulic splitter, get done an hour earlier, and use that hour to go to the gym and lift weights. But am I actually ahead of where I am if I take the extra hour to split with a maul, knowing I am getting a good workout, and enjoying the satisfaction of doing the work myself?

A modern tractor and haycutter can do the work of many men with scythes when it comes to cutting hay. But does that mean the scythe requires more labor? On the surface, yes, but what if we look deeper? The tractor and haycutter were assembled in a factory, and the labor of the workers must be factored in. Before they were assembled, they were designed, so we must include the labor of the engineers, product designers, and product testers. We must account for the labor that built the components, that loaded the shipping containers of components onto rail cars, ships, and semi trucks, and that transported them to the factory. We must also account for the transport of the finished product to the dealer, the construction of both the factory and the dealership, and the labor of the repair technician at the dealership. We must must account for the labor involved in drilling for, refining, and transporting the petroleum that fuels the tractor. At this point, is the scythe still require more labor? I don’t know, but let’s assume it does. We now must factor in the enjoyment factor. Is the labor in the windowless factory mindlessly assembling parts equal to the labor of swinging a scythe in the open air with a breeze on your back and the birds singing overhead? What about the labor of the repair technician, or the truck driver, or the billing clerk for the farm cooperative’s fuel depot? How do the scythe and the tractor with haycutter compare when all the hidden labor and it’s quality is factored in? I don’t know, but I do know that the scythe comes out considerably better in a true accounting than in the superficial one often used.

So how do I currently navigate all of this? Well, I own two vehicles, a zero-tun lawnmower, a chainsaw, a gas weed-eater, a laptop, and a smart phone. Clearly, I am not a total Luddite. However, I do try to make conscious choices. When I put up the frame for my greenhouse, I used a hand saw to cut the joinery, and used nails and a hammer rather than screws and a screw gun. I try to limit my use of automobiles–any trip to a store (except the auto parts store) generally waits until I or the wife is already going to either work or church. We do not have internet service at our house, except for the ability to use a cell phone as a hotspot, which we turn off when not in use. I am considering buying a small (~125cc) motorcycle to ride to work and back to reduce our consumption of gasoline. I built a clothesline to reduce our use of the electric dryer. I installed a non-electric pellet stove to reduce our dependency on our natural gas furnace. We use kerosene lamps for our lighting needs in the winter. I try to take it one step at a time and become less reliant on technology each year.

Perhaps someday I will have a small farm, and breed mules. Maybe I’ll be able to do this somewhere close enough to church that we can do without a car. Maybe I’ll be able to limit electricity and internet to a small office in a shed on the property. But for now I just try to make one small step and a time, to use my labor instead of a machine where I can.